Um texto de 2001, nunca publicado, que decidi recuperar hoje…

(escrito como resumo para a conferência Borders, Displacement and Creation, na FLUP, Setembro de 2011))…

Thicker lines, sensible spaces: Art in-between borderlines (2011)

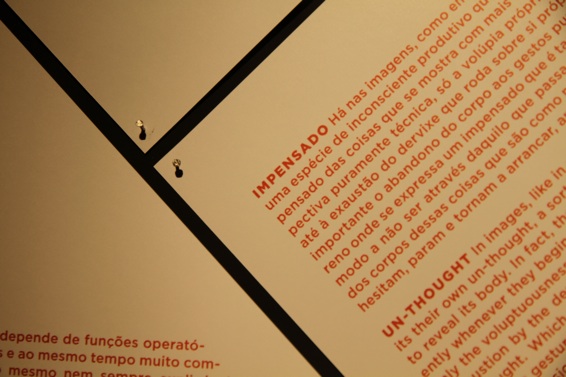

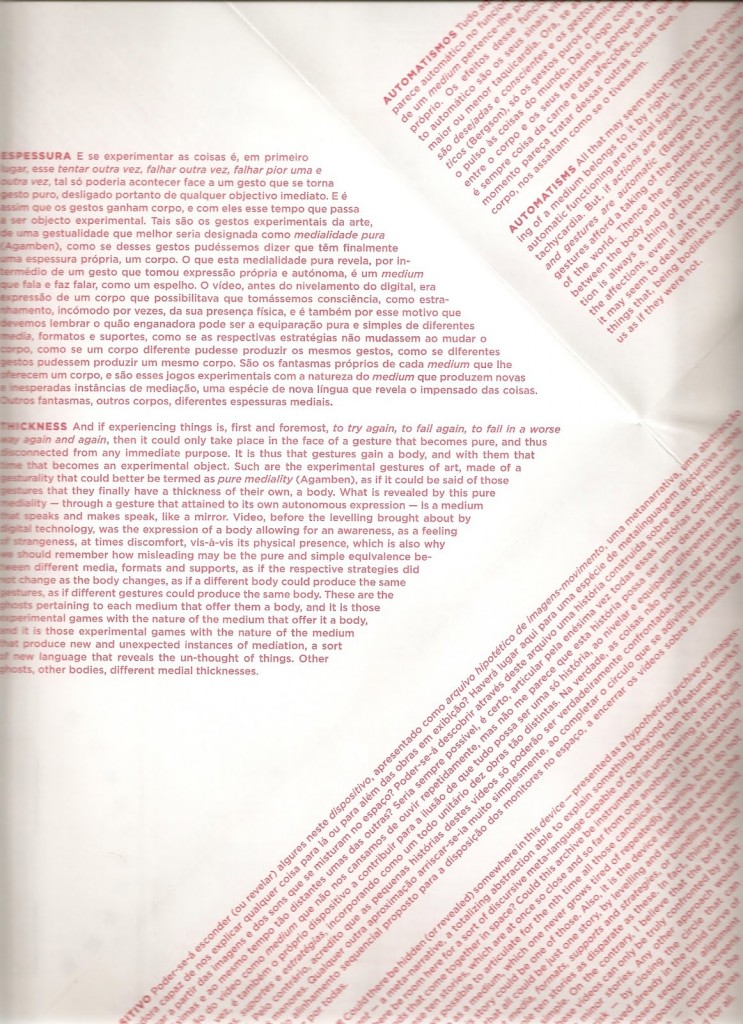

We have learned from euclidian geometry that a line is one-dimensional, a figure without any width nor depth, a breathless flow of infinite length. In fact, as we all know since our school days, a line is an abstraction, unless we draw it, moment when it stops being a line to become something concrete in front of our eyes. To draw a line on a sheet of paper is an experience that makes us aware of the instability of any trace, call it a line or any other name. First, such a trace (line) is always limited by the surface on which we are drawing it; second, any trace (line) depends also on the drawing material we are using. A soft pencil will return a thick, dark and irregular trace with a perceptible texture; a hard one will give us a thinner, lighter and more regular trace; a pen or a small brush with indian ink will offer perhaps a even more surprisingly result. Plus, we can use a ruler or further objects to help us on that task; or chose to trace, for instance, a dotted or slashed line, among many other possibilities. Each one of our choices, and the combination between all of them, together with those unwanted and unexpected situations that arise from any material activity — the phenomenology of making to which one day Robert Morris referred to as being so important to art — , will shape our topological experience of lines (traces) as something founded on a bodily variability. And don’t forget that even those lines that we draw with our mouse or track pad, those apparently abstract lines who temporarily inhabit our computer files will at some point materialize themselves on our laptop screen or on our printer, only way to escape the false misery of a clean and ideal world made of 0s and 1s, chips and algorithms.

So, lines are only abstractions before their actual materialization. From that moment they escape their ideal nature and become an impure body with a strong variability. This is something quite obvious but anyhow very important to every material practice — as with visual or plastic arts —, a terrain where experience and experimentation take the lead.

*

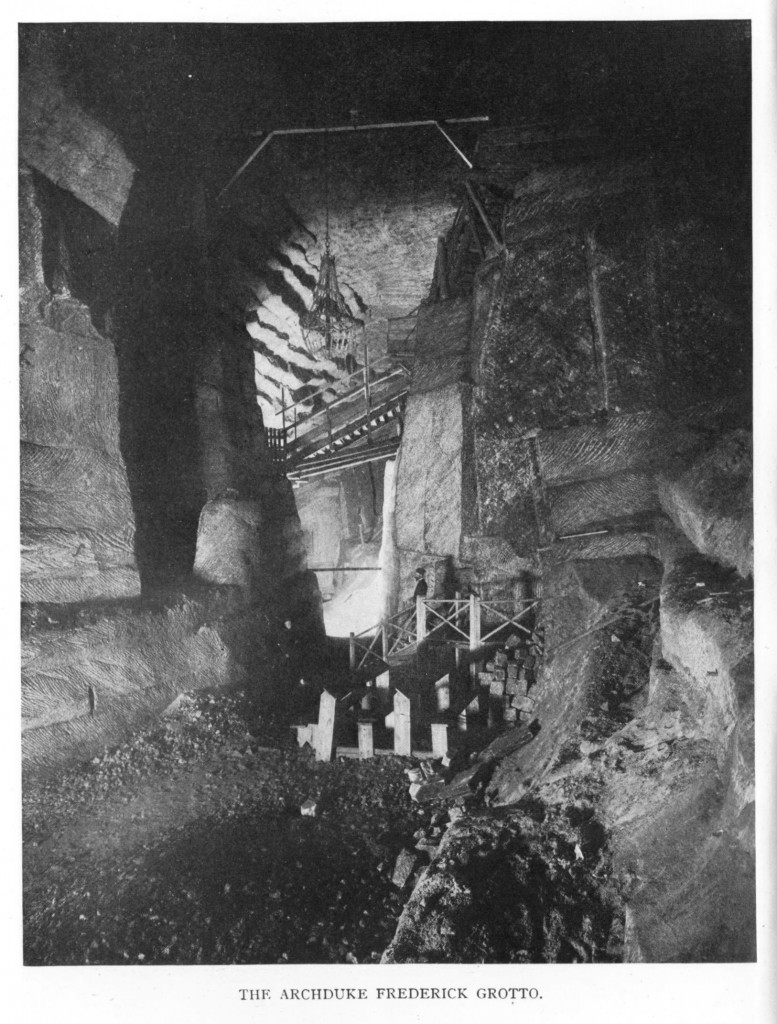

When we think about borderlines we are not far from the situation I have just resumed. Following the ideal and abstract nature of any line, borderlines are also pure fictions, yet they are usually explicitly or implicitly traced over maps and territories, books and speeches, ideas and actions. Each borderline must always become material to become effective. Even more, sometimes those lines must be mediated to become real. In other words, a figure of speech and symbolic investment such as a borderline must become a trace to become operative, to become a subject of experience. There is a passage from Goethe’s Elective Affinities (1809) which I use to quote on this subject, when Goethe writes about Eduard spending his evenings and early mornings drawing the contours and hatching the heights of his land, shading and coloring his possessions on a sheet of paper, to discover that only then, after taking shape in front of his eyes, was he really coming to know his land, that only then did they really belong to him. It is not by accident that we could found such a relation between mediation and landscape in one of the most important figures of Romanticism. In fact, we cannot detach the invention of modern landscape from the material conditions of its mediation, as we cannot separate modern politics from the actual materialization of lines over maps and other real objects.

In a similar context, all those modern spaces of enclosure deeply analyzed by Foucault, such as the hospital or the school, the factory or the prison, the barracks or the asylum, are spaces of confinement or, at least, spaces with precise borderlines, spaces precisely delimited: we always now when we are entering one of them, basically because their borderlines are somehow explicitly visible. Such spaces of otherness and enclosure permanently enunciate the condition of being in and out, here and there.

We all recognize the general crisis of those spaces and dispositifs (to recall the foucauldian term) characteristic of disciplinary societies, something announced by Deleuze on his famous “Postscript on the societies of control” more than twenty years ago. We now face a more insidious type of control: diffuse, undulatory, adaptive and apparently unbounded. In the middle of this dispersion and reconfiguration of old institutions and its localized and fixed apparatus of domination, the former idea of borderline or boundary seems old-fashioned. Borderlines enclose spaces and define them as self-contained entities. All along this genetic mutation from discipline to control, from fixed structures to volatile and unnamed ones, borderlines and boundaries ceased to exist, at least as we were used to understand them. And the recent developments in the so-called global financial, economic and political crisis are among the symptoms of those changes. This crisis helped things that we somehow took for granted to suddenly collapse, starting with all those borderlines we laboriously invented during the last couple of centuries. The problem is not the end of certain modern structures still surviving among us, but the generalized simulacrum of consensus which announces the end of politics and the rise of a new pragmatic approach to the art of governing, consequently killing any idea of political action or even critical thought. The problem is the false and elusive disappearance of boundaries and borderlines from maps and territories, books and speeches, ideas and actions. Now invisible, borderlines are perhaps even more effective.

**

The favorite sport of modern art was to trespass borders. The quest for the exterior tended to be central to aesthetic experimentation and artists mostly embodied an ideal of transgression and resistance over normative impositions. The permanent attraction for exteriority and otherness kept art and artists moving in and out, a movement which sometimes caused every borderline to be crossed several times and in several directions. For that reason, today the centrifugal reshaping of boundaries and the attraction for the exterior can be understood as an integral part of modern tradition. But, then, a new problem arises: how to deal with the disappearance of exteriority and the exhaustion of the modern ideal of transgression? The apparent final victory of aesthetics erased most of the borderlines traced between art and life, art and non-art. The kantian finality without end doesn’t seem to serve as a productive distinction anymore, both by art’s commodification and dilution as an unproductive activity or by the massive designification of the world, where everything now seems to relate to aesthetics, from nails to surf, or from yoga to dental care.

Again, the question is not to cry over a lost paradise or a disappearing world. The deeper question is how to understand art and its autonomous sovereignty in the middle of all these changes? How to maintain art as a radical activity in a context where the capacity to cross borderlines or the ability to live in the verge of self-dissolution is no more a distinctive quality, a context where borderlines are diffuse, invisible and more operative than ever before?

What I want to suggest is that, during the last few decades, and as a direct answer to this otherwise insurmountable question, artists are more likely to be found inhabiting borderlines, transforming those lines in thicker and stronger aesthetic spaces, and not only metaphorically. Trespassing explicit borders is no longer productive. In a moment when borderlines seem to be disappearing all around, the possibility of giving a body, a texture and a material presence to those lines is probably an important political task for our near future. And assuming that art is something made from its own making, artistic practice is certainly a perfect terrain to experiment with the bodily variability of lines (traces).

Balancing deductive and inductive methods, in my brief presentation will try to approach these questions through a quick analysis of some recent art works by artists such as Francis Allÿs, Gabriel Orozco or Joachim Koester and Matthew Buckingham.

***

Every time I wonder about the powerful and magic presence of maps I recall the image of Eduard drawing his own, tracing lines and coloring shapes on a sheet of paper, not to retrieve cartography as a mastery over time and space but more likely as an elective affinity, as an intensive experience of affection and, finally, as a real political engagement. Maps are material evidences of our personal and collective topology; on their best, maps measure intensively our relation with the world. Certain maps are ways to draw a cartography of life itself.